What is selective mutism?

Selective mutism (SM) is an anxiety disorder characterised by the inability of children to speak in certain social contexts, such as school, extracurricular activities, community events and sports, despite being able to communicate verbally at home and in other settings. Although children with SM may exhibit talkative behaviour within the confines of their immediate family and specific environments, they often remain silent or extremely restricted in their speech when faced with social situations, depending on factors such as the people present, the location, the activity and their own comfort level.

Even small changes or stepping out of their comfort zone can trigger a significant shift in their willingness to speak. For example, a child with SM may engage in lively conversations with their parents at home, communicate confidently in a grocery store aisle, or express themselves in a restaurant, but promptly become silent upon the arrival of a neighbour, the presence of an adult or peer in the same grocery store aisle, or when approached by a waiter to take an order. This pattern of selective silence profoundly affects their ability to effectively express their needs and fully participate in various aspects of life, including school, social interactions, extracurricular activities and their community.

While it is natural and adaptive for children to have varying levels of verbal participation and to be more reserved when encountering unfamiliar people or situations, it is important to distinguish between typical behaviour and selective mutism. Even the most sociable and outgoing children may experience occasional moments of silence or reluctance to speak that do not significantly affect their daily functioning.

However, children with SM consistently show a reluctance to speak in certain social scenarios that require communication, such as at school, while retaining verbal abilities in other contexts, such as at home with family members. The resulting silence or reluctance to speak adversely affects their daily lives.

Take our quiz: Is it a case of shyness or selective mutism?

Does your child tend to freeze up or be unable/unwilling to speak in certain circumstances? Answer a few questions to gain a better understanding.

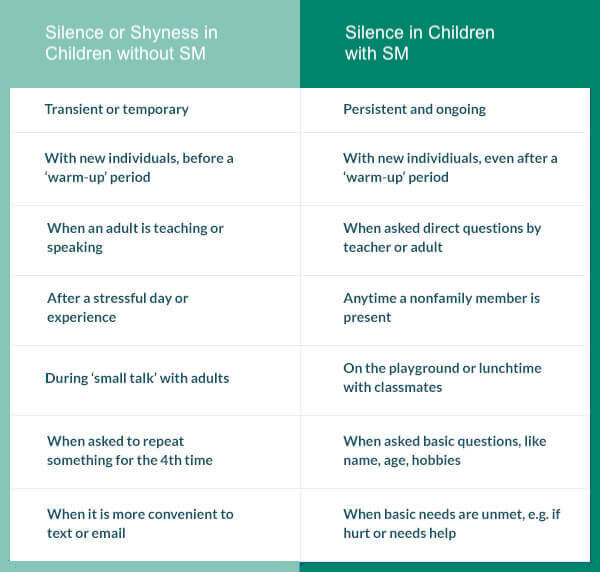

Take The QuizUnfamiliarity with selective mutism (SM) can lead parents, carers, teachers and health professionals to misinterpret a child’s social silence as mere “shyness” or a temporary phase. Shyness typically involves initial reticence, especially in new or unfamiliar situations, and often requires a short period of adjustment. However, children without SM who are shy will usually begin to engage and communicate after a warm-up period.

In contrast, a child with SM may remain stubbornly silent even after extended periods of familiarisation, such as multiple play dates with peers or years in the same school environment. They may also struggle to respond when friendly peers or adults ask for basic personal information such as their name, age or interests. The impact of SM goes beyond social interactions; it affects a child’s ability to seek help, express basic needs or communicate when hurt or in distress. The table below provides a comparative overview.

Occasionally, both adults and children may misinterpret the selective silence of children with SM as ‘rudeness’ or deliberate defiance. It is important to understand that children with SM experience anxiety and that their silence stems from concerns about social evaluation, fear of making mistakes and uncertainty about being accepted and liked. Given the inherent communication difficulties associated with SM, individuals with this condition may be branded as “the one who does not speak”.

Without proper identification and treatment, they are at increased risk of developing social anxiety disorder and other mental health conditions, while continuing to struggle with SM as they transition into adolescence and adulthood. This trajectory creates a persistent pattern of social silence that significantly impacts their social, emotional, academic and occupational well-being.

Read this important article about SM in teenagers and adults.

Symptoms and common features

Selective mutism (SM) manifests as an anxiety-driven condition characterised by limited verbal communication, primarily observed in children who are otherwise able to speak in familiar environments. To diagnose SM, the essential symptom of persistent silence in social settings must be present for at least one month, or longer if it occurs within the first year of schooling. It is important that the inability to speak is not due to a lack of knowledge or comfort with the language required in the given social situation. It is important to rule out primary language or communication disorders, as well as other conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment recommendations.

In addition to a persistent reluctance to speak, children with SM often have a rigid posture, facial expressions that are frightened or anxious, limited eye contact and delayed responses, even when a clear preference or response is evident. They may also experience worry, anxiety, stress and physical complaints such as pain or discomfort. Reluctance to separate from parents or preferred peers, sensory sensitivity and inflexible behaviour are other characteristics of people with SM.

Within the spectrum of SM, the communication styles of affected children can vary. Some may severely restrict both verbal and non-verbal communication in social situations, characterised by closed mouths, minimal eye contact and expressionless faces. This limited display of cues leaves others uncertain about their thoughts, feelings and unmet needs.

Others rely solely on non-verbal communication methods such as nodding, smiling, pointing, writing, signing or miming to interact. While nodding, pointing and writing can meet many needs, over-reliance on non-verbal means reduces their opportunities to practice and become comfortable with speaking.

Some people with SM may make sounds, noises or unintelligible utterances (e.g. grunts, mumbles, animal sounds) rather than using understandable words.

Whispering or adopting an altered voice (e.g. lower or higher pitched, robotic, animal-like) is another common communication pattern observed in many children with SM. Whispering or altering their voice can provide a sense of reduced exposure and anxiety compared to speaking in their typical voice, although it puts strain on their vocal cords and requires additional effort.

Finally, some children with SM may be able to speak clearly and audibly in certain environments or with certain people outside their home, while remaining non-verbal in other contexts.

Treatment options for selective mutism reviewed

There are two main approaches to treating selective mutism: psychological/behavioural treatments and pharmacological interventions. However, the primary approach to treating selective mutism is psychological/behavioural treatment. In cases where children do not respond to these methods, pharmacological interventions may offer some potential benefits.

Psychological/behavioural treatment

Among the various psychological/behavioural treatments available, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) stands out as an evidence-based treatment for childhood anxiety disorders, including selective mutism. CBT focuses on teaching children coping strategies, such as changing their thinking patterns, and relaxation techniques. It also involves gradually guiding children to confront their fears through exposure therapy. Behavioural principles such as shaping, contingency management and modelling are used by clinicians. Graded exposure is particularly effective.

The gold standard intervention for selective mutism is behavioural therapy, as it has the strongest research base (Wong, 2010). Typically recommended as an initial treatment option, behavioural therapy aims to reduce anxiety and avoidance, improve language and verbalisations, and reduce oppositional or attention-seeking behaviour (Cohan, Price & Stein, 2006). This approach includes techniques such as shaping, stimulus fading, behavioural exposure and contingency management (Bergman, 2013; Cohan et al., 2006).

- Shaping involves breaking down the target behaviour into incremental steps towards the end goal. For example, parents may use shaping to help their child learn to ride a bicycle, with each step building on the previous one. In the context of selective mutism, the steps may involve progressing from non-verbal behaviours to speech, including mouth relaxation, blowing air through the mouth, making sounds, speaking audibly, answering forced-choice questions and eventually using full sentences.

- Stimulus fading involves changing one variable at a time to facilitate the transfer of speech from familiar communicators, places or situations to new ones in which the child may not currently be able to speak. For example, the fading process might begin with the child talking to a parent while playing a game in an empty classroom, and gradually introduce the presence of a teacher who becomes more involved in the interaction, offering verbal participation and asking forced-choice questions. Finally, the parent’s presence is faded out and the child communicates independently.

- Fading incorporates key elements of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), which was originally developed to address disruptive behaviour in children and adapted for children with selective mutism (PCIT-SM). PCIT-SM focuses on teaching parents communication skills, promoting problem-solving skills, encouraging consistency and persistence, and providing positive attention and praise for desired child behaviours. During PCIT-SM, a trained clinician provides live coaching to the parent via a headset while observing the parent-child interaction from a separate room. The therapy has two phases: Child Directed Interactions (CDI) and Verbally Directed Interactions (VDI).

- CDI serves as a warm-up phase in which the parent enthusiastically follows the child’s lead during play, refraining from giving instructions, commands, criticism or prompts to speak. In VDI, parents are trained to use planned questions and eventually commands. They are encouraged to praise verbal behaviour and to use effective prompts to stimulate speech, such as forced-choice questions and open-ended questions. For example, a forced-choice question in a restaurant might be, “Would you like pizza or pasta for lunch?”

- Exposure therapy uses a fear hierarchy or ladder to systematically expose children with selective mutism to different situations that require nonverbal communication or speech. The difficulty of these situations is gradually increased over the course of treatment. Positive reinforcement is used to reward the child’s engagement according to a collaborative behavioural plan involving the service provider, parents, child and, where possible, members of the school team. Throughout treatment, the ultimate goal is to generalise language and social gains across as many individuals, settings, and situations as possible (Raggi, Samson, Loffredo, Felton & Berghorst, 2018).

- Contingency management uses reward systems to celebrate brave behaviours while minimising attention to problematic behaviours.

Behavioural interventions are typically delivered through individual or group therapy sessions on a weekly or near-weekly basis. In addition, children with selective mutism may attend intensive therapy camps such as Brave Buddies, Mighty Mouth and Confident Kids Camp. These camps typically provide around thirty hours of behavioural intervention over the course of a week, often in a simulated classroom environment, and include activities such as scavenger hunts and visits to local restaurants.

Pharmacological treatment

While psychological/behavioural treatments take precedence in the management of selective mutism, pharmacological interventions, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Prozac and Zoloft, have shown promise as medical treatments for anxiety and mood disorders. Although research on the use of SSRIs for selective mutism is limited, the available data suggest positive outcomes, particularly for children who do not respond to psychological/behavioural interventions (Carlson, Mitchell, & Segool, 2008).

The role of pharmacological methods in the treatment of selective mutism remains largely uncertain due to the lack of large-scale experimental trials in this area. Most of the available research on medication and selective mutism is based on small sample sizes. However, a recent review highlighted SSRIs as the most promising medication option for children with selective mutism (Carlson, Mitchell & Segool, 2008). Medication is usually considered as a secondary treatment approach when children do not respond to behavioural therapy.

It may also be considered when children are severely impaired by selective mutism, have comorbidities, or have a strong family history of selective mutism or anxiety. The aim when using medication is to use it in the short term alongside behavioural interventions. It should be noted that there are currently no medications approved by the FDA specifically for the treatment of selective mutism. Potential side effects should be carefully considered when considering medication as part of the treatment of childhood selective mutism.

Prevalence and relevant background information

Selective mutism affects approximately 1% of the general population (APA, 2013; Bergman, 2012). Despite being classified as a rare condition, these prevalence rates are comparable to or higher than those reported for autism spectrum disorders. Selective mutism typically presents at an early age, usually between 2.5 and 4 years of age. Identification of the condition often occurs when children are around 5-6 years old, suggesting a delay of 1-3 years between symptom onset and recognition (Kotrba, 2015).

Formal assessment and treatment for selective mutism typically occurs between the ages of 6.5 and 9 years, which coincides with approximately four years of schooling (Kotrba, 2015). These delays can lead to the development of ingrained speech/non-speech patterns, and put children at risk of being stigmatised as the child who does not speak. In addition, such delays can lead to a continued diagnosis of selective mutism into adolescence and adulthood.

Selective mutism is more common in female children than in males, by a ratio of almost 2:1 (Kumpulainen, 2002; Garcia, 2004). This difference may reflect an accurate representation or may be influenced by societal expectations that place a greater emphasis on verbal communication in females, leading to increased awareness and concern when they exhibit limited speech.

Comorbidities and associated factors

Anxiety disorders, characterised by fear, anxiety and related behaviours, underlie selective mutism. It is not uncommon for children with selective mutism who experience fear and anxiety around speech to also experience fear and anxiety in other situations. These children may experience anxiety in social contexts, difficulty separating from parents, and fear of certain objects or situations (e.g. bees, darkness), leading to additional mental health diagnoses.

Common comorbidities include social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and specific phobias (APA, 2013). Social anxiety disorder is particularly common, with 75-100% of children with selective mutism meeting criteria for this disorder (Yeganah, Beidel, Turner, Pina, & Silverman, 2003). Given the overlap in symptoms and comorbidities, it is important for clinicians to distinguish whether additional symptoms are due to selective mutism or require an additional diagnosis.

Selective mutism is often comorbid with a range of communication disorders (APA, 2013). In one study, 32% of children had receptive language difficulties and 66% had expressive language difficulties (Klein, Armstrong, Shipon-Blum, 2012). While it is possible for a child to have both a communication disorder and selective mutism, a diagnosis of SM is inappropriate if the lack of speech is directly attributable to the communication disorder. However, there are cases where these disorders co-exist, such as when a child refrains from speaking in front of others because of concerns about how their communication disorder affects their speech (e.g. “I sound funny”), which warrants a diagnosis of selective mutism.

Causes and risk factors

Selective mutism, like most psychological disorders, does not have a single cause, but rather results from a combination of temperamental, genetic, environmental and neurodevelopmental factors (Muris & Ollendick, 2015). Children with selective mutism are often described as behaviourally inhibited from infancy (Gensthaler et al., 2016). Anxiety in general has a strong genetic basis and tends to run in families, with heritability estimates ranging from 25% to 50% (Czaijkowski, Roysamb, Reichborn-Kjennerud & Tambs, 2010).

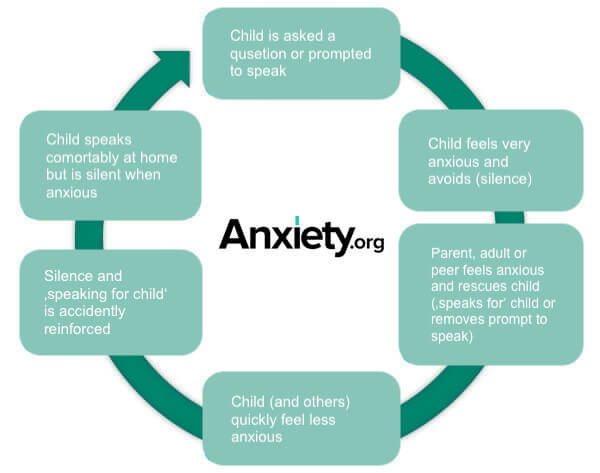

Among individuals with selective mutism, 70% have a first-degree relative with a history of social anxiety disorder and 37% have a first-degree relative with a history of selective mutism (Chavira, Shipon-Blum, Hitchcock, Cohan, & Stein, 2007). For children with selective mutism, social interactions or situations that require talking can trigger the typical fight-flight-freeze response seen in anxiety disorders. Subsequently, these reactions or behaviours may be exacerbated when children avoid speech as it provides relief from the anxiety-provoking situation.

This cycle of speech avoidance and subsequent anxiety reduction can be seen as an ‘effective’ avoidance strategy (Young, Bunnell & Beidel, 2012). Well-meaning parents, siblings and others often unintentionally reinforce the child’s silence by speaking on their behalf or removing the need to speak. For a visual representation, see the behavioural conceptualisation diagram below.

Research has suggested potential differences in sound transformation and processing in children with selective mutism, linking specific parts of the brain and ear to differences in how they perceive their own voice and other sounds compared to typically developing children (Henkin & Bar-Haim, 2015; Muris & Ollendick, 2015).

In addition, several risk factors for selective mutism have been identified, including family dysfunction, trauma, school environment, bullying, immigrant status, and social/developmental delays (Muris & Ollendick, 2015). However, it is important to note that none of these risk factors can be considered a direct cause of the development of selective mutism.

Cultural differences

To date, no specific cultural differences in children with selective mutism have been documented. However, it is important to distinguish between selective mutism and the period of non-verbal communication (known as the ‘silent period’) that immigrant children experience when learning the language of the host country. In second language acquisition, children typically go through four distinct stages:

1) prolonged silence when expected to speak in the second language, 2) practice and repetition of words in the second language, 3) a silent period of quiet practice of words and phrases in the second language lasting from weeks to six months, and 4) confident use of the second language in public (Samway and McKeon, 2002). Bilingual immigrant children with selective mutism usually do not progress beyond stage three due to concerns about their perceived ability in comparison to others, resulting in a prolonged period of silence.

Symptoms of reluctance to speak may be more pronounced and persistent in the second language; however, bilingual immigrant children consistently struggle to speak in situations that require speech, affecting both languages. This inability to speak is disproportionate to the child’s language competence and proficiency (Toppelberg & Collins, 2010; Toppelberg et al., 2005).

Tips for parents and teachers

Parents, teachers, school counsellors, school psychologists and coaches have an important role to play in helping children overcome selective mutism.Parents are encouraged to share information about selective mutism with other adults, coaches and family members with whom their child does not speak. Collaboration with the child’s school is strongly recommended to ensure consistent delivery of behavioural strategies and interventions across school, home and after-school activities.

If possible, parents should arrange for their child to visit the new classroom before the start of the school year.This will allow the child to become familiar with the environment without the pressure of interacting with other children or adults.

Similarly, meeting the child’s teacher before the first day of school can help the child feel more comfortable with a new adult.While the aim may not be immediate verbal communication, any spontaneous speech should be promptly praised in a simple way (e.g. “Thank you for telling me”) before the conversation is brought back to the topic or activity.

Ongoing communication between parents and teachers is essential to assess progress and address any barriers to achieving goals.If the child is joining a new after-school activity, it is beneficial for the child to meet the coach or instructor beforehand.

Parents can share the following tips with adults and people the child does not speak to:

- Always give specific praise for verbal behaviour. For example, “Thank you for asking to go to the toilet” or “I liked the way you asked Cindy to borrow a crayon”.

- Allow 5-10 seconds of silence after asking a question. Avoid jumping in to answer, give the child a chance to respond. Show comfort with a short pause.

- Use forced-choice questions (e.g., “Is this red, blue, or something else?”) instead of simple yes/no questions (e.g., “Is this red?”) or open-ended questions (e.g., “What colour is this?”). Children with selective mutism are more likely to respond to forced-choice questions and may freeze or struggle with open-ended questions.

Finding the right provider – questions to ask

Competence in evidence-based treatment:

- Have you received direct training in evidence-based treatments for children with selective mutism (SM), such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and behavioural approaches?

- Have you received further training from reputable sources such as the Selective Mutism Training Institute (SMTI) or under the supervision of recognised SM experts (e.g. Steven Kurtz, Child Mind Institute)?

- Are you open to seeking ongoing consultation with trainers or graduates of the SMTI or other SM experts during my child’s treatment if you do not have direct training in evidence-based SM treatment?

- Are you familiar with the treatment of childhood anxiety using CBT and behavioural approaches, given that SM is classified as an anxiety disorder?

- Can you provide references or demonstrate familiarity with the treatment of SM?

Experience and outcomes:

- How many children with SM have you treated and what have been the outcomes?

- Given the limited awareness and specialisation in SM, it is important to note that only a fraction of mental health providers have expertise in this area.

- Do you have experience of treating childhood anxiety using CBT or behavioural techniques?

- SM treatment is usually short term, lasting a few months. Experienced providers often see improvements in a child’s speech and language within the first few sessions of treatment.

Behavioural techniques:

- What specific behavioural techniques are used to target speech in children with SM?

- Effective techniques in the treatment of SM include fading, shaping and exposure therapy (see the Treatment section of this article).

Involvement of parents, carers and siblings:

- What is the role of parents, carers and siblings in the treatment process?

- While their support is crucial, it is important to avoid inadvertently reinforcing anxiety-provoking behaviours.

- Are you able to provide training for parents, teaching them about the courage cycle, the avoidance cycle, and strategies to reduce accommodating behaviour?

- Can you show them how to introduce new communication partners and environments?

Working with schools:

- How do you work with schools to facilitate language for children with SM?

- Do you carry out direct observations of the child in a school setting?

- Do you have experience in coaching school staff and conducting fade-in or shaping sessions to promote speech with peers and staff?

- Can you provide strategies for promoting speech in small group and whole class settings? (See the Tips for Parents and Teachers section of this article.)

Generalising skills to everyday activities:

- How do you support children with SM to increase their speech outside of therapy sessions, including in their daily activities and tasks?

- Do you include exposure exercises in community settings, focusing on areas where children with SM often need additional support?

- Can you provide examples of how you facilitate speech in real-life situations, such as ordering food in a restaurant, initiating play with peers in a park, or requesting assistance from a librarian?

Recommended Readings and Resources

Websites

- Selective Mutism Association

- Child Mind Institute

- Child Anxiety Network

- Selective Mutism Foundation

- Selective Mutism Information and Research Association

Books

- Selective Mutism: An Assessment and Intervention Guide for Therapists, Educators, and Parents by Aimee Kotrba

- Overcoming Selective Mutism: A Parent’s Field Guide by Aimee Kotrba and Shari Saffer

- The Selective Mutism Resource Manual by Maggie Johnson

- Helping Your Child with Selective Mutism: Practical Steps to Overcome a Fear of Speaking by Angela E. McHolm, Charles E. Cunningham, and Melanie K. Vanier

- Helping Children with Selective Mutism and Their Parents: A Guide for School-Based Professionals by Christopher Kearney

- Exposure Therapy for Treating Anxiety in Children and Adolescents A Comprehensive Guide by Veronica Raggi, Jessica Samson, Julia Felton, Heather Loffredo, and Lisa Berghorst

- Understanding Katie by Elisa Shipon-Blum

- Maya’s Voice by Wen-Wen Chang

- Charli’s Choice by Marian Molnar

Applications

- Mindfulness and Mediation: Headspace, Calm

- Deep breathing: Breathe2Relax

- Interactive games requiring speech: Magic Jinn, Screaming Chicken

Sources

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM–5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

- Bergman, R. L. (2013). Treatment for children with selective mutism: An integrative behavioral approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2013.846733

- Carlson, J. S., Mitchell, A. D., & Segool, N. (2008). The current state of empirical support for the pharmacological treatment of selective mutism. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(3), 354.

- Chavira, D. A., Shipon-Blum, E., Hitchcock, C., Cohan, S., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Selective mutism and social anxiety disorder: all in the family?. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(11), 1464-1472.

- Cohan, S. L., Price, J. M., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Suffering in silence: Why a developmental psychopathology perspective on selective mutism is needed. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(4), 341–355. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703- 200608000-00011

- Czajkowski, N., Roysamb, E., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., & Tambs, K. (2010). A population based family study of symptoms of anxiety and depression the HUNT study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1-3), 355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.006

- Gensthaler, A., Khalaf, S., Ligges, M., Kaess, M., Freitag, C. M., & Schwenck, C. (2016). Selective mutism and temperament: the silence and behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 25(10), 1113-1120.

- Henkin, Y., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2015). An auditory-neuroscience perspective on the development of selective mutism. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 1286-93. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2015.01.002

- Klein, E. R., Armstrong, S. L., & Shipon-Blum, E. (2013). Assessing spoken language competence in children with selective mutism: Using parents as test presenters. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 34(3), 184-195.

- Kotrba, A. (2015). Selective mutism: An assessment and intervention guide for therapists, educators & parents. Pesi Publishing & Media.

- Kumpulainen, K. (2002). Phenomenology and treatment of selective mutism. CNS drugs, 16(3), 175-180.

- Muris, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2015). Children who are anxious in silence: A review on selective mutism, the new anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clinical Child And Family Psychology Review, 18(2), 151-169. doi:10.1007/s10567-015-0181-y

- Raggi, V. L., Samson, J. G., Felton, J. W., Loffredo, H. R., & Berghorst, L. H. (2018). Exposure Therapy for Treating Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: A Comprehensive Guide. New Harbinger Publications.

- Samway, K.D., Mckeon. D. (2002) Myths about acquiring a second language. In: Miller Power B, Hubbard RS., editors. Language Development: A Reader for Teachers. 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp. 62–68.

- Toppelberg, C. O., & Collins, B. A. (2010). Language, culture, and adaptation in immigrant children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 19(4), 697-717.

- Toppelberg, C. O., Tabors, P., Coggins, A., Lum, K., Burger, C., & Jellinek, M. S. (2005). Differential diagnosis of selective mutism in bilingual children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(6), 592-595.

- Vecchio, J., & Kearney, C. A. (2009). Treating youths with selective mutism with an alternating design of exposure-based practice and contingency management. Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 380-392. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.005

- Wong, P. (2010). Selective Mutism: A review of etiology, comorbidities, and treatment. Psychiatry, 7(3), 23-31.

- Yeganeh, R., Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., Pina, A. A., & Silverman, W. K. (2003). Clinical distinctions between selective mutism and social phobia: an investigation of childhood psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(9), 1069-1075.

- Young, B. J., Bunnell, B. E., & Beidel, D. C. (2012). Evaluation of children with selective mutism and social phobia: A comparison of psychological and psychophysiological arousal. Behavior Modification, 36(4), 525-544. doi:10.1177/0145445512443980

Lindsay Scharfstein, Ph.D., is a Licensed Clinical Psychologist and founder of the Rockville Therapy Center, a private practice based in the DC Metro Area. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Central Florida and completed her Pre-Doctoral and Post-Doctoral fellowships at the Yale University Child Study Center. Dr. Scharfstein is the director of the Confident Kids Camp-DC Metro, a 1-week intensive treatment program for children with selective mutism. She has also launched training/consultation programs for professionals, including the Selective Mutism Training Series and the School Refusal Training Institute.

Dr. Scharfstein conducts specialized psychological assessments for individuals with anxiety and related disorders, to help obtain accurate diagnoses and develop personalized treatment plans. She is extensively trained in evidence-based treatments, including Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Trauma-Focused CBT, Exposure and Response Prevention for OCD, Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT), Habit Reversal Training for hair pulling and skin picking, Family Therapy, Parent Training/Support Sessions, and Social Skills Training. She has particular expertise in the treatment of selective mutism and social phobia (social anxiety disorder), and treatments aimed to enhance social and emotional functioning.

Dr. Scharfstein provides treatment in individual, couples, family, group, and intensive therapy ‘camp’ formats. She engages in ongoing communication with family, school, and community systems to foster collaborative relationships and optimize treatment success and quality of life.

Additionally, Dr. Scharfstein offers educational workshops within the community and presents at national conferences. She also has several peer-reviewed journal publications, including in Behavior Research and Therapy, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, and Behavior Modification.

Victoria is currently a student in the clinical psychology doctoral program at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She earned her Master of Professional Studies degree from the University of Maryland, College Park and her Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Central Florida.

She has clinical experience working in roles in a wide variety of settings including inpatient psychiatric units, community mental health centers, and private practice. She hopes to become a licensed clinical psychologist specializing in the treatment of child and adolescent anxiety disorders; her specific interests include evidence-based treatment of selective mutism and anxiety-based school refusal.

Carla E. Marin, Ph.D., is an Associate Research Scientist and Clinician at the Yale Child Study Center Anxiety and Mood Disorders Program. Dr. Marin is an experienced clinician in the assessment and treatment of anxiety and mood disorders, including selective mutism. She specializes in cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, and young adults.

Dr. Marin’s research interests focus on mechanisms of pediatric anxiety treatment outcome, cognitive and attentional processes in the etiology of anxiety, and the role of culture and ethnicity in this population. She consults with and provides professional development workshops to school personnel. Dr. Marin has received extensive training in complex data analytic techniques and provides her statistical expertise in the Anxiety and Mood Disorders Program’s research projects.

Dr. Marin received her Ph.D. from Florida International University in 2010. She was born in Nicaragua, but was raised in Miami, Florida after her family migrated to the United States in the late 1980s. She is fully bilingual in English and Spanish.