Emotional discomfort as death approaches is common but not inevitable

It comes as no surprise to learn that terminally ill individuals often feel quite anxious about impending death. What is perhaps more surprising is that not everyone feels this way. For those who are better able to manage anxiety, dying may be a more peaceful, comfortable experience.

Anxiety about death has always been a concern for people in the final stages of terminal illness, as well as their family, friends, doctors, and nurses. Until recently, however, research on death anxiety has often only focused on the experiences of doctors and nurses. Our own recent study is among the first to look at death anxiety in hospitalized patients who are approaching the end of their life.

Even Healthy Individuals May Experience Death Anxiety

In nursing literature, death anxiety is more precisely described as “a vague uneasy feeling of discomfort or dread generated by perceptions of a real or imagined threat to one’s existence”, and has been extensively studied in the fields of nursing and psychology.1-6 These studies have shown that younger patients suffer far more death anxiety compared to older patients.6-9

Religion also plays a part in decreasing levels of death anxiety: anxiety levels have been shown to be lower in individuals with religious beliefs compared to those without such beliefs.10 The relationship between death anxiety and gender also appears to be strong – studies have shown that females are likely to have higher levels of death anxiety than males.11 Moreover, the levels are higher in older females than in any other group.5

Studying Death Anxiety In Patients Near Death

Though extensive research on death anxiety has already been conducted, the population examined in most of these studies included college students, church goers, and nurses.6,12,13 Patients in the final stages of different illnesses or those nearing death have rarely been included in research.14 Most studies conducted in the hospital environment measured the death anxiety of nurses who were providing care to patients, rather than measuring the death anxiety of the patients themselves.2 In our work, we focused on hospitalized patients nearing death or at the end of life (EOL).15

Our study was based on data from a nursing electronic health record (EHR) system called HANDS (Hands on Automatic Nursing Documentation System).16 Data was collected over a period of three years (2005-2008) from nine different hospital units in four hospitals. For each patient in the HANDS system, the medical record contained nursing diagnoses for the patient’s problems, along with nursing outcomes (or goals) related to these diagnoses. In addition, the dataset contained demographic information on the patients and nurses. When a patient was admitted, a care plan for that patient was created that included current ratings for each nursing outcome and an expected rating for that outcome.

Different interventions were then used to reach the expected outcome rating. These care plans were updated by the nurses at the end of every shift, and the goal was considered achieved if the rating in the final shift was greater than or equal to the expected rating set in the first shift. In our study, the focus was primarily on the “comfortable death” outcome, because it was the most commonly recorded goal outcome among the 462 patients diagnosed with death anxiety.15 For most people, a comfortable death was highly valued. However, death anxiety makes it hard for a dying person to finish life with the dignity of a comfortable death.

In our study, we took into account a patient’s age, length of stay, and the average years of nurses’ experience to determine whether any of these characteristics improve the chances of meeting the “comfortable death” goal. Additionally, we grouped nursing diagnoses and interventions that appeared in patients’ care plans in order to determine whether these diagnoses or interventions had any effect on the comfortable death outcome.

Younger Patients Showed Higher Levels of Unresolved Death Anxiety

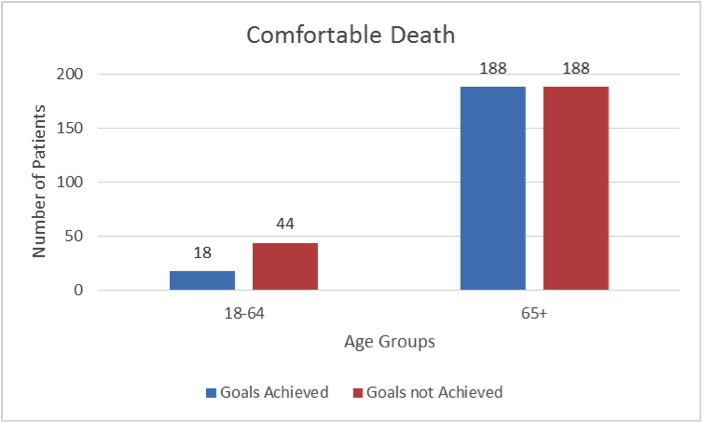

As mentioned previously, comfortable death was the most commonly assessed outcome, present in the care plans of 438 patients. However, only 47% of the patients with a recorded comfortable death outcome achieved their expected goals. After analyzing the data, it was observed that only 29% of the younger patients (age < 65 years) met their goal (Figure 1), while nearly 50% of the older patients achieved their goal.

These results could suggest that nurses may be ignoring or overlooking the fact that younger patients also suffer from death anxiety. Furthermore, younger patients may not be as ready to engage in life-closure activities as compared to older individuals, who may be more accepting of imminent death. We speculate that remaining life closure activities could be a reason for unresolved death anxiety among younger patients.

Figure 1: Relationship of Patient’s Age to Comfortable Death Outcome. © 2014 HANDS Team

Length of Stay and Nurse Experience Predicted Comfortable Death

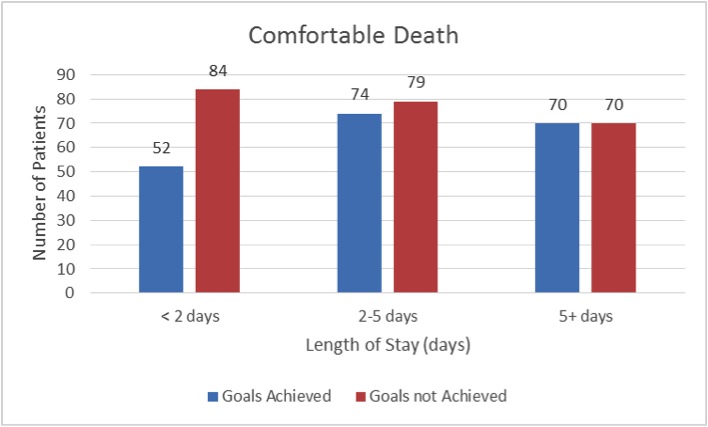

Our results also indicated that a patient’s length of stay was associated with achieving the outcome goal or desired state. Specifically, the number of patients meeting the comfortable death goal increased as the patient’s length of stay increased (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Relationship of Patient’s Length of Stay with Comfortable Death Outcome© 2014 HANDS Team

When we reviewed the data based on hospital units, we observed that most of the patients (71.2%) diagnosed with death anxiety belonged to two different Gerontology units. The nurses working on these specialty units typically had expertise in handling issues common among older patients, including death anxiety. In these units, if the care was being provided by experienced nurses (with over two years of nursing experience), the patients were more likely to achieve their comfortable death goal (54.8%). On the other hand, only 48% of the patients achieved their goal if they received care from relatively less experienced nurses.15

Helping Patients Die More Comfortably

This study has revealed several interesting trends in the outcomes achieved by patients near the end of life and experiencing death anxiety. The findings provide preliminary evidence that the nurse’s years of experience, a patient’s length of stay, the type of care unit (such as gerontology versus medical surgical), and the age of the patient appear to influence whether the patient achieves a comfortable death when they have a diagnosis of death anxiety.

Although additional research is underway, these findings can be applied at little cost to an organization or detriment to the patient. For example, we suggest that, whenever possible, patients near the end of life be assigned to units in which nurses have experience with caring for dying patients. We also recommend that alerts be added to the electronic health records to remind nurses that young patients who are at the end of life may require special attention to achieve comfortable death.

Finally, the length-of-stay finding suggested that patients seem to benefit from an environment that is stable during the last days of life. This means that nurses and other health care workers should consider limiting the changes, like transfers, discharges, and readmissions, in venue for end-of-life patients, because these changes seem to interfere with comfortable death.

Nurse educators can also learn from the study findings and take steps to improve nursing students’ knowledge and skills, in order to further helping dying patients have comfortable deaths. Two sources of high-quality, inexpensive educational materials for nurse educators include:

- ELNEC (End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium, www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec)

- TNEEL (Toolkit for Nurturing Excellence at the End of Life, www.tneel.uic.edu/tneel.asp or www.tneel.uic.edu/tneel-ss)

With improved education, it is possible that nurses with less experience can achieve similar comfortable death outcomes as nurses with over two years of experience.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by Grant Number 1R01 NR012949 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Nursing Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute for Nursing Research. The final peer-reviewed manuscript is subject to the National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy.

We would also like to gratefully acknowledge and thank the following as co-researchers on this project:

-

- Muhammad K. Lodhi, PhD Candidate, Department of Computer Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Umer I. Cheema, PhD Candidate, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Janet Stifter, PhD, RN, Department of Biobehavioral Health Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Gail M. Keenan, PhD, RN, FAAN, Professor and Annabel Davis Jenks Endowed Chair for Teaching and Research in Nursing Clinical Excellence, College of Nursing, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL Adjunct Professor, Departments of Health Systems Science and Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Diana J. Wilkie, PhD, RN, FAAN, Professor, Harriet H. Werley Endowed Chair for Nursing Research, Director, Center of Excellence for End-of-Life Transition Research, Department of Biobehavioral Health Science and Adjunct Professor, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Yingwei Yao, PhD, Research Associate Professor, Department of Biobehavioral Health Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Rashid Ansari, PhD, Professor and Head, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

Disclosure

The HANDS software that was used in this study is now owned and distributed by HealthTeam IQ, LLC. Dr. Gail Keenan is currently the President and CEO of this company and has a current conflict of interest statement of explanation and management plan in place with the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Sources

1-NANDA International. (2007). Paper presented at the nursing diagnosis and definitions: 2007-2008, Oxford, United Kingdom.

2-Kisvetrova, H., Klugar, M., & Kabelka, L. (2013). Spiritual support interventions in nursing care for patients suffering death anxiety in the final phase of life. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 19(12), 599-605.

3-Lehto, R. H., & Stein, K. F. (2009). Death anxiety: An analysis of an evolving concept. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 23(1), 23-41.

4-Abdul-Khalek, A. M. (2005). Death anxiety in clinical and non-clinical groups. Death Studies, 29(3), 251-259.

5-Depaola, S. J. G. M., Young, J. R., Neimeyer, R. (2003). Death anxiety and attitudes towards the elderly among older adults: The role of gender and ethnicity. Death Studies, 27(4), 335-354.

6-Keller, J. W., Sherry, D., & Piotrowski, C. (1984). Perspectives on death: A developmental study. The Journal of Psychology, 116(1), 137-142.

7-Bengston, V. L., Cuellar, J. B., & Ragan, P. K. (1977). Stratum contrasts and similarities in attitudes towards death. Journal of Gerontology, 32(1), 76-88.

8-Feifel, H., & Branscomb, A. B. (1973). Who’s afraid of death? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 81(3), 282-288.

9-Fortner, B. V., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1999). Death Anxiety in older adults: A quantitative review. Death Studies, 23(5), 387-411.

10-Alvarado, K. A., Templer, D. I., Bresler, C., & Thomas-Dobson. (1995). The relationship of religious variables to death depression and death anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 202-204.

11-Harrawood, L. K., White, L. J., & Benshoff, J. J. (2008). Death anxiety in a national sample of United States funeral directors and its relationship with death exposure, age, and sex. Omega– Journal of Death and Dying, 58, 129-146.

12-Wen, Y. H. (2010). Religiosity and death anxiety. The Journal of Human Resource and Adult Learning, 6(2), 31-37.

13-Schwartz, C. E., Mazor, K., Rogers, J. Y. M., & Reed, G. (2003). Validation of a new measure of concept of a good health. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6(4), 575-583.

14-Lo, C., Hales, S., Zimmermann, C., Gagliese, L., Rydall, A., & Rodin, G. (2011). Measuring death-related anxiety in advanced cancer: Preliminary psychometrics of the death and dying distress scale. Journal of Pediatric Hematology Oncology, 33(Supplement 2), S140-S145.

15-Lodhi, M. K., Cheema, U. I., Stifter, J., Wilkie, D. J., Keenan, G., Yao, Y., . . . Khokhar, A. A. (2014). Death anxiety in hospitalized end-of-life patients as captured from a structured electronic health record: Differences by patients and nurse characteristics. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 7(5), 224-234.

16-Keenan, G., Yakel, E., Yao, Y., Xu, D., Szalacha, L., Tschannen, D., & Wilkie, D. J. (2012). Maintaining a consistent big picture: Meaningful use of a web-based POC EHR system. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 23(3), 119-133.

Dr. Ashfaq Khokhar is the Chair of The Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) at The Illinois Institute of Technology where he also serves at the rank of Professor. He also holds adjunct appointment in the Departments of Computer Science, ECE, and Health Information Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC).

Dr. Khokhar received his B.Sc. in Electrical Engineering from the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan, in 1985, his M.S. in Computer Engineering from Syracuse University, in 1989 and Ph.D. in Computer Engineering from University of Southern California, in 1993. After his Ph.D., he spent two years as a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Sciences and School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Purdue University. In 1995, he joined the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Delaware, where he first served as Assistant Professor and then as Associate Professor. In Fall 2000, Dr. Khokhar joined UIC in the Department of Computer Science and Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and served at the rank of Professor and Director Graduate Studies till Summer 2014.

Dr. Khokhar’s research centers on computational biology, health care data mining (particularly nursing care data), content-based multimedia modeling, retrieval and multimedia communication, context-aware wireless networks, and high-performance algorithms. He is considered a leading expert in the area of high-performance solutions and Big Data. He has graduated over 20 Ph.D. students in the last 10 years. His research is currently supported by multiple awards funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Institutes of Health. In the recent past Dr. Khokhar’s research has also been supported by the United States Army, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Dr. Khokhar has published over 250 technical papers and book chapters in refereed conferences and journals in the areas of healthcare data mining, wireless networks, multimedia systems, data mining, and high performance computing. He is a recipient of the NSF CAREER award in 1998. He has received numerous outstanding paper awards, and has served as program chair and technical program committee members of leading IEEE/ACM conferences.

He is a Fellow of IEEE for his contributions to multimedia computing and databases.