The two different approaches can work together to effectively treat anxiety disorders

Anxiety from the perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) can work together with the Western approach to maximise the benefits for patients.

Anxiety disorders, a common mental and emotional condition, affect a significant number of people worldwide. In the United States alone, one in three people will experience some form of anxiety disorder during their lifetime. This ancient affliction has plagued humans since the dawn of our species, stemming from the primal fear of self-preservation, whether it be a concern for food or the fear of becoming prey. Traditional Chinese medicine, with roots going back thousands of years, has developed theories and methods to help individuals cope with anxiety.

Western medicine relies on empirical diagnoses formulated by experts in the field. Anxiety disorders include conditions such as panic disorder and social anxiety disorder, which are categorised on the basis of symptoms and specific fears. Although recent research has explored dimensional approaches to symptoms, the utility of such approaches remains unclear. Transdiagnostic theories that offer a dynamic and individualistic perspective on research, diagnosis and treatment, such as the ABC theory of anxiety, require further empirical validation. This approach views anxiety as a dynamic interplay of alarms, beliefs and coping strategies that shape clinical presentation and reflect the interaction of underlying neural networks.

Contemporary research, particularly in neuroimaging and neurochemistry, is providing a wealth of information about the neural circuits, neurotransmitters and synaptic connections associated with these disorders. Anxiety disorders are thought to be polygenetic and significantly influenced by environmental stressors.

Within the Western scientific approach, treatments for anxiety disorders are typically studied in selected patient groups that may not be representative of the broader anxiety population due to unrealistic selection criteria. Clinical groups often have a significant overlap of multiple diagnoses, and statistical analyses of symptom associations and treatment outcomes within these diagnostic groups form the basis of scientific understanding.

However, clinicians encountering these disorders are confronted with diverse patients presenting with unique variations. Diagnoses often overlap and manifest in different combinations within the same individual. Treatment options are sometimes wrongly dismissed because of significant placebo responses in patients. Despite its status as the gold standard in contemporary medicine and psychology, the Western scientific approach still has significant limitations, with approximately 20-30% of patients remaining symptomatic for various reasons.

In contrast, TCM takes a fundamentally different approach that may challenge Western scientific perspectives. Chinese medicine takes a holistic view of the body and its functions, viewing all elements as interrelated parts of a whole. No entity can be isolated from its relational context with other entities; nothing exists in isolation.

Consequently, both physical and mental/emotional problems are seen as interrelated, arising from disharmonies in the “Five Minds” (energies, as distinct from divinity) and their associated “5 Zhang Organs”.

The Five Minds encompass different aspects of the human psyche within Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM):

- Shen – the mind and unifying spirit.

- Hun – the non-corporeal spirit.

- Po – the corporeal spirit, associated with grief, sorrow and worry.

- Yi – the intellect and thinking.

- Zhi – the will, associated with fear.

These spirits reside in the “5 Zhang Organs”, the heart, liver, lungs, spleen and kidneys. The vital life force known as qi facilitates communication between these energies. For example, stagnant liver qi can manifest as anger.

This individualistic approach relies heavily on assessing these energies in a patient prior to treatment. The treatment itself involves a combination of acupuncture and the use of ancient herbal remedies.

Initially, this approach raised eyebrows in the Western medical community because of the complexities of diagnosis and treatment, which made it difficult to conduct double-blind experiments and statistical analyses. TCM faced the challenge of explaining its theories to Western scientists and convincing the medical community to accept it alongside conventional medical practice.

However, progress has been made in recent years as scientists have sought to ‘westernise’ TCM. Positive descriptive outcomes documented in case reports have contributed to its mainstream acceptance. With specific licensing requirements and quality controls in place, the training and practice of TCM has been normalised and supported by various insurance companies. The inclusion of TCM in the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) of the National Institutes of Health and the World Health Organization (WHO) has further solidified its scientific recognition.

As TCM has gained mainstream recognition over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in the number of patients with anxiety disorders seeking help from TCM practitioners. Although Chinese and Western medicine have fundamentally different approaches, both describe the human body as their subject.

During treatment with a Chinese medicine practitioner, patients may encounter unfamiliar diagnoses. For example, they may be diagnosed with ‘spleen dampness’, ‘liver qi stagnation’ or ‘heart fire’. Although Chinese medicine uses different terminology and lacks the concepts of the nervous and endocrine systems, it deals with the same conditions.

Mental and emotional dysregulation is understood in terms of disturbances in Shen, the energy of the heart. Anxiety also involves disturbances in Po, the energy of the lungs. Interestingly, typical symptoms of anxiety, such as palpitations and shortness of breath, coincide with these disturbances. Recent studies have even found abnormal breathing patterns in patients with panic disorder.

In addition to energetic disturbances, physiological disturbances manifest as stagnant qi in corresponding meridians. These meridians resemble blood vessels, with 12 main pathways through which qi flows. In addition, associated “Patterns of Disharmony” in the related Zhang Organs must be treated and rebalanced to achieve lasting results.

Here is an example of a clinical case demonstrating the application of the above theories, as worked on by Chinese medicine practitioner Polina Bowler:

- “Zoe“, a 40-year-old patient, sought treatment for severe anxiety which had resurfaced after a long period of abstinence. She was experiencing panic attacks three times a week and sudden wrist pain that she had never experienced before. Other symptoms included palpitations, chest tightness, nausea, shortness of breath, profuse sweating, poor sleep and irritability with outbursts of anger. Zoe had successfully managed her lupus for three years with minimal medication. During the consultation, she reported that she had been under considerable stress in the last two months due to a hasty move caused by a verbally abusive and threatening landlord. Although she had managed the situation and completed the move, she found herself overwhelmed by anxiety once the stress had subsided. Through careful observation of her facial expressions, tone of voice, pulse assessment and tongue examination (integral to Chinese diagnosis), Bowler identified how the recent stressful events had triggered intense emotions of worry, anger and frustration in Zoe. In order to cope with the challenges, she had suppressed these emotions, inadvertently restricting the smooth downward flow of Liver Qi, which is responsible for maintaining the overall flow of Qi in the body. This constriction of Liver Qi resulted in Liver Qi stagnation, causing a reverse flow from down to up, which affected her Lung energy, Po, resulting in chest tightness. Over time, the accumulated congested liver energy, Hun, generated heat in the upper body, contributing to feelings of restlessness, irritability, palpitations, anxiety and insomnia, collectively known as Heat in the Heart and Disturbance of Shen, the Mind. In Western terms, this condition corresponds to anxiety. The excessive heat also depleted her fluids, aggravating Zoe’s already compromised kidneys from lupus (as chronic diseases weaken the kidneys in TCM), and ultimately culminating in panic attacks, as fear is the associated emotion of the kidneys, and panic attacks manifest as intense, unfounded fear.

Bowler diagnosed Zoe’s anxiety as primarily due to liver qi stagnation, heart heat and kidney deficiency. Her treatment plan involved the use of specific acupuncture points to facilitate the movement of liver qi, suppress heart heat, strengthen the kidneys and calm the shen (mind). In addition, Bowler prescribed a modified Chinese herbal formula called Chai Hu Long Gu Mu Li Tang, tailored to Zoe’s weakened kidneys. She recommended an increase in omega-3 oils, a low-sugar, dairy-free diet, and the use of ashwagandha for a month and clary sage oil applied to the inside of Zoe’s wrists. After three treatments within ten days, Zoe experienced a remarkable reduction in anxiety and her panic attacks stopped.

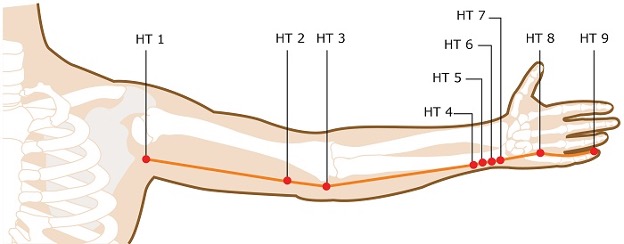

One remarkable aspect of TCM that never fails to impress is how intricately interconnected everything is. Nothing happens by chance; it simply requires the ability or knowledge to see the relationships between different factors. For example, Zoe’s wrist pain was directly related to Heart Heat. The superficial heart meridian originates at the heart, passes through the armpit, runs along the inner elbow, down the medial side of the forearm, crosses the wrist and palm and ends at the inner side of the little finger. The improper flow of Heart Qi caused stagnation in the meridians around her wrist. Have you ever noticed that when a person is nervous they tend to fidget with their fingers? Remarkably, Zoe’s wrist pain disappeared after the first treatment.

Anxiety comes in many forms and is experienced differently by different people. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) does not categorise diseases or prescribe standardised treatments. Instead, by identifying each patient’s imbalances, a TCM practitioner creates an individualised treatment plan that evolves as signs and symptoms change. TCM’s personalised approach is proving highly effective in treating anxiety, as no two people are alike.

As TCM gains more respect and acceptance within the Western medical community, a Westernised approach to medical and psychological disorders has been developed, even though TCM makes no distinction between them. This approach deliberately excludes the spiritual aspects of TCM (relating to life forces, not deities), while retaining mechanistic strategies that can be tested in clinical trials. However, removing the traditional understanding of energetic forces and the highly individualistic approach compromises treatment outcomes.

Nonetheless, such adaptation enhances the ability of scientists to evaluate TCM treatment outcomes and potentially compare them with Western approved treatments for these conditions. This compromise has to be accepted. Many clinical trials have already been conducted, and the results are optimistic. Acupuncture points such as Qiuxu (GB-40), Baihu (DU-20), Yintang, Neiguan (P-6), Shenmen (HT-7), Teaching (LV-3), Sanyinjiao (SP-6), Zusanli (ST-36), as well as scalp acupuncture with electrical stimulation and ear acupuncture with points such as Shen Men, Tranquilliser and Relaxation, have been used in the treatment of anxiety.

These acupuncture points are known for their powerful sedative and calming effects on Shen (the mind, spirit) and have been used for centuries to treat Shen disorders. The conclusion of these studies is that “acupuncture is a common clinical practice for the treatment of anxiety disorders, and scientific data have demonstrated its statistically significant efficacy”.

This ongoing work suggests that Western medicine may have something to learn from TCM, particularly in the individualised treatment of unresponsive patients. However, it is worth noting that success stories published as case reports in major scientific journals are currently rare. To be fair, treatment-resistant patients with severe anxiety often undergo multiple trials of medication and behavioural therapy. Experienced Western practitioners who treat anxiety disorders typically use individualised approaches that take into account symptom dynamics, environmental factors, family dynamics and other relevant factors. Therefore, regardless of the treatment philosophy used, patients benefit from an individualised approach.

Chinese herbs and traditional herbal formulas have also become an area of extensive research in the last decade for the treatment of depression and anxiety in TCM. Ginkgo Biloba (a renowned Chinese herb first documented in a Chinese book around 2800 BC), Chai Hu (Bupleurum), Suan Zao Ren (Zizyphi Spinosi seed), Da Zao (Jujube date), Shen Di Huang (Rehmannia root), Ginseng and Gan Cao (liquorice root) are among the herbs known for their ability to alleviate the restlessness, irritability and emotional disturbance associated with anxiety.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) offers several herbal formulas for the treatment of anxiety and other psychiatric disorders, including

- Ban Xia Huo Po Tang (pinellia and magnolia formula)

- Xiao Chai Hu Tang (Minor Bupleurum decoction)

- Jia Wei Xiao You San (Bupleurum and Tangkwei formula)

- Gan Mai Da Zao (Licorice Jujube Combination)

- Chai Hu Jia Long Gu Mu Li Tang (Bupleurum, Dragon Bone and Oyster Shell Formula)

These formulas, along with others, have a common application in treating anxiety. However, they are very different and must be tailored to the individual’s constitution and energetic imbalances. By using this approach, both the symptoms and the underlying causes of anxiety can be significantly improved.

Similarly, Western science has increasingly incorporated herbal medicine and nutritional supplements into the treatment of anxiety. In addition, individual genetic analysis is being used to match psychiatric drugs to a person’s genetic code, taking into account relevant mechanisms of action and liver metabolism.

In conclusion, a combination of Western and TCM approaches, respecting both, can be highly effective in the treatment of anxiety, including difficult and treatment-resistant cases. Close collaborative care using all available tools will enable clinicians to help a greater number of people manage their anxiety and improve their quality of life.

Sources

- Aung KH et all (2013) Medical Acupuncture, Volume 25, Number 6, 2982

- Sniezek, D.P., and I.J. Siddiqui, Acupuncture for Treating Anxiety and Depression in Women: A Clinical Systematic Review, Medical Acupuncture, 2013, Jun 25 (3): 164-172

- Lei Liu, Changhong Liu, et al, Herbal Medicine for Anxiety, Depression and Insomnia,

- Current Neuropharmacology 2015, Jul 13 (4):481-493

- Bystritsky A et al, Current Diagnosis and Treatment of Anxiety (2013) P T., Jan; 38(1):30-57.

- Bystritsky A, Spivak NM, Dang BH, Becerra SA, Distler MG, Jordan SE, & Kuhn TP. Brain Circuitry Underlying the ABC Model of Anxiety. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021;138:3-14.

- Yanhua Zhang, Transforming Emotions with Chinese Medicine, State University of New York Press, NY, 2007.